|

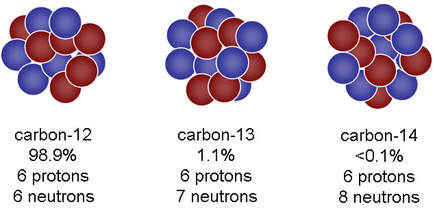

When I was a brand new professor... Before an exam. Students: Can you tell us what to study? Me: Everything from Chapter 1 to 6. Plus all the stuff covered in the last 5 weeks. Plus all the wisdom coming out of my mouth. Anyway you should figure it out on your own. After the exam. Me: Grrrrrrrrrr. I can't believe everyone bombed the problem on the exponential decay of Carbon-14! A colleague: Did you tell them it's important? Me: Well, they should have known!!! It's in Chapter 6 and we covered all of Chapter 6. Colleague: No you didn't. I visited Nicole Watson's Human Biology class before fall semester ended. It was a fantastic class! Nicole is such an effective communicator, and it has a lot to do with her many verbal cues: - This is very important... - That is a tricky question... - You should know that... - etc. By constantly communicating goals and expectations, Nicole does more than presenting information: she guides students and actively engages them. As a result, the class is focused, productive and clearly enjoying the experience. Not all teachers make efforts in telling students about goals and expectations, or about what is important and what to study. (Putting them in a 25-page syllabus and never emphasizing them in class is hardly an effort.) But why not? Some instructors think that if we tell the students what topics to study, they will only study those topics and ignore the rest. (Wouldn't it be great if students would actually study exactly what we ask of them?) If the students are so good at taking such directions, it makes even more sense that we give them a great deal of specific directions, instead of vague ones like studying all of Chapter 9. Some instructors believe that learning how to learn is part of the learning process. (Sorry for the tongue twister.) In that case, let's guide the students through this learning process. Don't just hope that they would figure it out on their own before failing a few classes along the way. For example, a 5-minute class discussion on what was important from last week, Family Feud style, might serve the purpose. In the end, students need to know about the goals and expectations. They need to know what to study. Not all of our students have the best preparation for college. They might have weaker academic background or studying skills, and they also take on responsibilities with jobs and family. However they try hard and study as much as they can. They would have a good chance to succeed, as long as we articulate the goals, specify what they should work on and help them work on those things. Back to my first-year teaching experience. If I could do it all over again, would I tell the students that the Carbon-14 problem would be on the test? If that makes them study and figure out the problem, then absolutely yes!

0 Comments

In ancient China, a doctor prescribed for the Emperor a rare medicine containing rhino horn powder. Since rhino horns were hard to find, the Emperor had to use bison horns which are slightly less potent. So why prescribe the rhino horns? First of all, they are best for this prescription, according to the doctor. Secondly, since the Emperor couldn't really get rhino horns, the doctor would have something to blame for if the Emperor does not get better. If we assign an amount of assignments that is unrealistic for most students to do, we are no different from the Chinese doctor in the story. Of course the more students study the more they learn, but what if most of them can't complete the assignments anyway? And when/if they fail, do we blame it on not finishing the assignments?

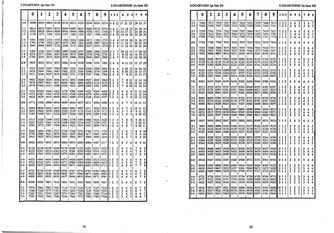

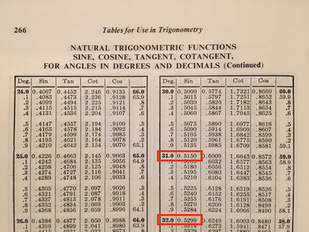

I began my career at Ramapo College of NJ, a liberal arts college and New Jersey's equivalent of U of M Morris. A rookie math professor, I would go over the exercises in the books and assign over 100 problems a week. I graded 4 or 5 of them, and left the rest unattended. When I moved to Metro State University, I focused only on essential topics and I assigned no more than 40 exercises a week. But with carefully designed assignments, my students at Metro State learned just as much even though they were less prepared and had less studying time than my students at the 4-year elite institution, A few general thoughts on creating assignments: (1) Have a clear agenda and set the priorities. What do we want to accomplish in an assignment? Is it about memorizing particular formulas? Drilling certain techniques? Understanding concepts? Making applications? Manipulating tricky skills? Modeling and problem solving? (2) Be efficient and effective. Keep control on the amount of work in each assignment. When an assignment gets too big, cut it to size according to your agenda and priorities in (1). (3) Integrate the assignments into teaching. Follow up on the agenda and the priorities: Have the students accomplished them? How do the assignments help them learn the content and prepare for tests? Community college students often juggle with jobs, personal and family life, and a challenging course load. Let's design effective assignments that would help them use their studying time efficiently and maximize their success. I went to high school in Taiwan in the late 1980s. Math lessons there included - Using logarithmic tables to estimate big numbers like 385,120,089*99,751,287. - Using trigonometric tables to evaluate functions like sin(31.58 degrees). My teacher said these skills are important for college. They might have been in his time, but by the time I went to college, I used computers for these calculations. For all the time I spent on perfecting the skills of using these tables, it was a lot of stress and little/no contribution to my higher learning. I was a math professor in the 2010s. Following a national trend of de-emphasizing the integral techniques in Calculus, I revised my Precalculus course by cutting topics such as partial fraction decomposition, a challenging skill whose only use is in a special integral technique. The positive impact was almost immediate. Students no longer stressed out about or lost points on these topics, and I was able to spend more time on other important topics. There are many ways to get directions on curriculum updates, such as - Advisory board on industry needs and trends (ITEC) - The curriculum of transfer destination 4-year universities (SciMath and ITEC), or - The recommendation by national associations (SciMath and ITEC) As we update curriculum to meet current standards and expectations, we also get an opportunities to remove certain cumbersome or out-of-date materials, and replace them with new and student-friendly ones. In many cases it might be an easy win for student success when we stop teaching, testing and punishing students on some less useful but really difficult stuff. Do you update your curriculum regularly? Imagine having a student who understands only 50% of the course content. When you approach the student and tell the student that he/she needs to do better, the student responds: "Are you saying that I should cheat?" That is definitely NOT the case. There are many things the student can do. For example, the student should try to improve on studying skills, work with tutors and peers, go to the professor's office hours, study longer or harder, etc. Improving courses success is a sensitive topic in higher education. Some instructors equate it to giving up academic rigor and inflating the grades to pass their students. They tend to suspect that their administrators want them to cheat.

That is also not the case. It's true that instructors are not solely responsible for student failures. And yes, there would always be students who lack preparation, who skip classes, who miss homework, and who don't appear to care at all. But as educators, we need to continue searching for ways to help students learn better. It is our commitment to the profession; it is our mission. This post is the first of a series of posts on the topic of improving course success. I do not claim to be an expert, and I welcome all questions and suggestions. The goal is for our school to keep thinking, discussing and taking actions on this important topic. Please join me on this conversation. |

AuthorDr. Ben Weng Archives

September 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed